What are Muskox?

Muskox are fascinating! Here is a snapshot of muskox history, conservation status, biology and behaviour, and other large mammals that co-exist with muskox on the Canadian Arctic tundra.

Pre-History

Muskox are large and hairy goat-like mammals with impressive horns, adapted to extremely cold grassland environments. There were originally two types of muskox in North America but only the tundra Muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) survived the megafuana extinction associated with the end of the last age.

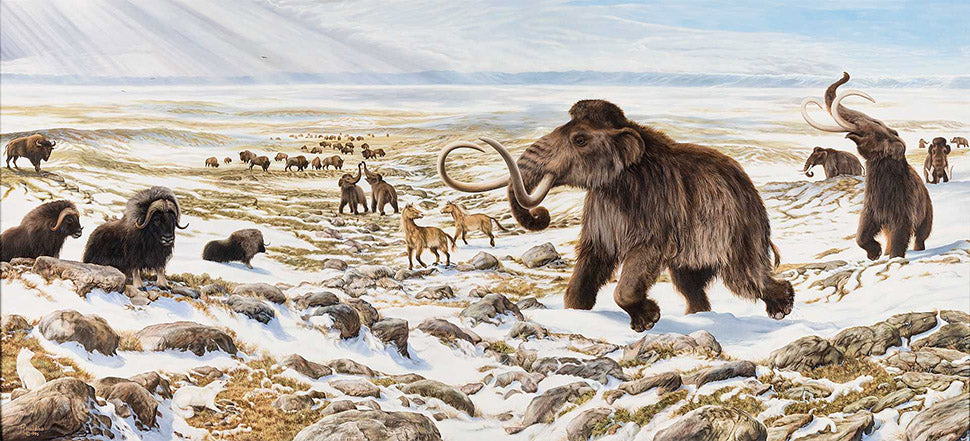

Muskox crossed the land bridge from Siberia to North America during the last ice age about 90,000 years ago and thrived with the Wooly Mammoth and other large mammals on the dry, cold grassland of Alaska and Yukon that was never glaciated called Beringia. Muskox also lived just south of the edges of glaciers, and their range expanded about 10,000 years ago as the circumpolar glaciers disappeared. They spread across the Arctic from Siberia, to Alaska, across the Arctic Archipelago and mainland tundra of Canada, to Greenland. At one time during the ice age, their range included areas as far south as Toronto, Canada.

Muskox are more closely related to sheep and goats than cows. Their closest living relative to a muskox is the goral, a ruminant that resembles a small grey goat that is found in the mountains of Asia.

Recent History and Conservation Status

By the early 1900’s the muskox population collapsed across the circumpolar north. This was caused by over-harvesting associated with the unregulated expansion of the whaling industry into remote arctic areas who required protein for the crew, and the unregulated expansion of the fur trade around the circumpolar Arctic. Muskox were extirpated almost everywhere, with the exception of a few inland arctic locations in Canada. A Canadian hunting ban was implemented in 1917. The population recovered several decades later in Canada to the point that muskox were transplanted from Canada back to Alaska, Northern Quebec, Greenland, and Russia. Today the muskox population has recovered in Canada. The highest and most dense natural population of muskox in the world is on the tundra near Kugluktuk, Nunavut. A limited and carefully managed hunt for muskox began again in arctic Canada in the 1980’s. Today, regulations permit no more than 4% of the population can be harvested for food. This harvest is conducted primarily by Inuit in Canada. Sub-populations of muskox fluctuate with natural conditions. Neither scientists nor Inuit know all the reasons for this but may include cycles of disease, predators, parasites, and feed availability.

Because the overall muskox population is relatively stable and carefully managed by government, products made of qiviut have no treaties affecting international trade.

Biology and Behavior

Muskox can be found in herds ranging from a few animals to more than 80. It is common for herds of non-dominant bulls to be in their own herds and old bulls sometimes wander alone. Baby muskox are born in early May before the snow melts. Muskox are ruminants and eat sedges and grasses. They will dig through deep snow to forage or move onto windswept ridges where grazing may be easier. In May their qiviut begins to shed, and it can remain tangled in the long guard hair of their coats for many months. The qiviut regrows before winter arrives. Both sexes grow horns but the horns of mature bulls are much larger. In the fall, mature bull muskox compete for mates. Unresolved arguments are settled with powerful, high speed, head-butting challenges, much like mountain sheep. Muskox do not migrate to avoid the long dark Arctic winters. Instead, they conserve heat using their powerful insulating coat of qiviut, and generate extra heat from symbiotic stomach bacteria that help digest plant based forage. As a result muskox can comfortably accommodate blizzards and -50 degrees Celsius winter temperatures. Tundra Grizzly Bears and Arctic Wolves are the main predators of Muskox. When Muskox feel threatened they will often create a defensive circle facing outwards with younger muskox protected in the middle.

Consistently, the largest muskox are found on the tundra plains on the northern Arctic coastline near Kugluktuk. No one really knows why, but the 24 hour sunlight in the summer combined with the fertile arctic soils produce a diverse and productive flora compared to other areas of the Arctic. Tundra grizzlies are common around Kugluktuk and maybe larger muskox can avoid grizzly predation easier.

Muskox are named Umingmaq in the Inuit language, which means ‘the bearded one’. Muskox have traditionally been used by Inuit: the meat for food; the hides for insulating sleeping mats, and; the horn and bone for tools and carvings.

Other Large Mammals that Co-exist Today with Muskox on the Tundra of Nunavut.

Although many large mega-fauna went extinct near the end of the last ice-age, there are still many large herbivores and carnivores that share the vast arctic tundra with muskox. Muskox live on the tundra of the mainland continent and some of the High Arctic Islands.

The most well known inhabitant of the tundra of Nunavut are Barren Ground Caribou. There are many caribou herds across the arctic and their population and distribution can vary greatly over time. Unlike muskox, caribou are always on the move and typically migrate large distances south seasonally in the fall to avoid the harshest part of the arctic winter.

The most common predators of Muskox are the Arctic Wolf, and the Tundra Grizzly Bear. Individual wolves are no match for an adult muskox, but large packs can cooperate to separate young, or tired muskox from herds in order to kill them for food. Tundra Grizzly Bear hibernate during the winter but are effective muskox predators the rest of the year. They are more carnivorous than other Grizzly populations elsewhere in North America. Western Nunavut has the highest population of tundra Grizzly Bear and their population is growing and expanding east and north. Wolverine also have a relatively high population on the mainland of western Nunavut. They are ferocious for their size, but are typically scavengers of muskox kills by other predators.

In addition to these animals there are many other mammal, bird, fish, insect and plant species in this pristine arctic environment.